How Open Data Changes the Way We Evaluate Information

Open data changes how we evaluate information by shifting trust from authority to verifiability, exposing tradeoffs, and improving long-term credibility through transparency and shared scrutiny.

Most discussions about information quality focus on accuracy. Is a number correct. Is a statement true or false. That framing is familiar but incomplete. In practice, the way we evaluate information depends less on individual claims and more on the systems that produce, distribute, and validate them.

Open data shifts attention from the surface of information to its underlying structure. It does not guarantee correctness. What it changes is the set of assumptions we are forced to make as readers, analysts or decision-makers. When data is open, evaluation becomes a process rather than an act of trust.

This distinction matters in fields ranging from public policy to journalism, research and technology. The presence or absence of open data alters how confidence is earned, how disagreement is resolved and how errors are discovered.

What “Open” Actually Changes

Open data is often described in terms of access. Data is published publicly, usually with a permissive license and documentation. That description is accurate but incomplete. The more consequential shift is epistemic.

When data is closed, evaluation is indirect. Readers assess credibility by proxy. They look at the reputation of the publisher, the authority of the institution, or the perceived expertise of the author. These signals are not meaningless but they are substitutes for direct inspection.

Open data removes some of those substitutes. It does not eliminate trust but it redistributes it. Instead of trusting a conclusion, readers are invited to trust a process. The data can be inspected, reanalyzed, combined with other sources or challenged on methodological grounds.

This does not mean most people will do those things. What changes is that someone can.

Evaluation Moves From Authority to Verifiability

In closed systems, authority carries disproportionate weight. If the underlying data is inaccessible, disagreement tends to collapse into status contests. Whose credentials matter more. Which organization has more legitimacy. These dynamics are familiar in regulatory reporting, corporate disclosures and even academic publishing.

Open data introduces a different mechanism. Authority still exists but it competes with verifiability. A well-known institution publishing weakly documented data is easier to question than a lesser-known group publishing clearly structured, reproducible datasets.

This does not create equality of influence but it introduces friction. Claims must survive contact with independent scrutiny. Errors are more likely to be surfaced not because everyone checks, but because checking is possible.

Over time, this changes incentives. Organizations that publish open data learn that clarity and documentation matter. Ambiguity becomes a liability rather than a shield.

Transparency Reveals Tradeoffs, Not Just Results

One of the quieter effects of open data is that it exposes tradeoffs that are often hidden in summarized outputs. Aggregated statistics tend to obscure uncertainty, exclusions and methodological choices. When only the final number is visible, evaluation focuses on whether that number feels plausible.

Open datasets force evaluators to confront what was left out, how categories were defined and where judgment calls were made. This often complicates interpretation rather than simplifying it.

That complexity is not a flaw. It reflects reality. Most real-world data involves compromises. Definitions evolve. Coverage is uneven. Measurement is imperfect. Open data does not fix these issues, but it makes them visible.

As a result, evaluation becomes less about declaring something right or wrong and more about understanding its limits. This encourages more careful use of information, especially in contexts where decisions carry long-term consequences.

Error Detection Becomes Distributed

Closed information systems rely on internal quality control. Errors are caught, if at all, by the same organizations that produced the data. This can work well in some environments, particularly where incentives are aligned and resources are abundant.

Open data enables a different model. Error detection becomes distributed. Independent analysts, researchers, journalists, and even automated tools can identify inconsistencies, anomalies or outdated assumptions.

This does not mean open data is constantly corrected by crowds. In practice, only a small subset of users engage deeply. But the possibility of external review changes behavior upstream. Data producers know their work can be examined, reused, and questioned outside its original context.

That knowledge tends to improve documentation discipline and methodological clarity over time. Not universally, but noticeably.

Context Becomes a Shared Responsibility

One common critique of open data is that it can be misinterpreted. Data taken out of context can support misleading conclusions. This risk is real, but it exists in closed systems as well. The difference is where responsibility lies.

In closed systems, context is controlled by the publisher. Interpretation is guided, sometimes narrowly. In open systems, context becomes a shared responsibility between producers and users.

Producers are incentivized to document assumptions, limitations and intended use cases. Users are expected to engage with that documentation and recognize the boundaries of what the data can support.

This mutual responsibility does not eliminate misuse but it changes how misuse is addressed. Disputes can focus on definitions, scope and methodology rather than speculation about hidden data.

Long-Term Credibility Over Short-Term Control

From an institutional perspective, open data often feels risky. It reduces control over narratives. It exposes imperfections. It invites critique.

Yet over the long term, openness tends to support credibility more effectively than control. Systems that rely on restricted access and managed interpretation accumulate trust debt. When errors eventually surface, confidence erodes quickly.

Open systems distribute that risk over time. Small corrections happen earlier. Disagreements are visible. Trust is built gradually through demonstrated openness rather than enforced authority.

This is not a moral argument. It is a structural one. In complex environments, no single organization can anticipate every question or use case. Open data allows evaluation practices to evolve alongside the data itself.

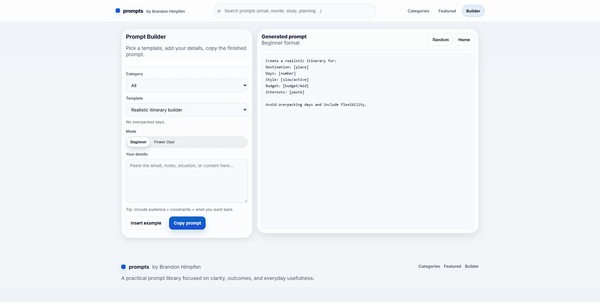

This site publishes a small collection of openly licensed datasets used in analysis, tools and public documentation.

Open Data Does Not Eliminate Judgment

It is important to be precise about what open data does not do. It does not remove the need for judgment. It does not guarantee neutrality. It does not make all interpretations equally valid.

What it does is make judgment more explicit. Assumptions can be examined. Methods can be compared. Competing interpretations can reference the same underlying material rather than talking past one another.

Evaluation remains a human activity, shaped by values, goals, and context. Open data does not replace that. It improves the conditions under which it happens.

Rethinking How Confidence Is Earned

Ultimately, open data changes how confidence is earned, not by insisting that everyone verify everything but by changing the baseline expectations of transparency.

When data is open, confidence grows from coherence. From documentation that matches structure. From methods that align with outcomes. From systems that can withstand inspection over time.

This is a slower path to trust, but a more durable one. It shifts evaluation away from declarations and toward understanding. In an information environment where certainty is often overstated, that shift may be the most valuable change of all.